Archive for March, 2015

British Antarctic Survey’s Halley Research Station in Antarctica.

Credit: Sam Burrell, British Antarctic Survey.

Research stations in Antarctica are gearing up to study how humans adapt to living in faraway, isolated locales – useful information to help orchestrate long-duration sojourns in space and setting up habitats on the Moon and Mars.

Halley Research Station in Antarctica is hosting key research to understand human adaptation to space travel. Depending on the time of year, the facility is home to between 13-52 scientists and support staff.

The “bitter truth” is that the station is about to embark on winter and will experience temperatures as low as -50 degrees Celsius and more than four months of darkness.

The Halley crew will live in the same conditions as teams being studied at Dome Concordia – a joint French/Italian station, located on the other side of the continent – except they will be at sea level.

Isolated and in the dark

The experiment aims to investigate how well previously trained skills are maintained over the nine months period of the winter, being completely isolated and in the dark for four months.

The mobile spaceflight simulator at Halley Station has been designed by the Institute of Space Systems (IRS) of the University of Stuttgart.

Winter generator mechanic, Steve Croft, inside the space flight simulator at Halley Research Station. Credit: Alexander Finch

Partnerships for Moon, Mars…and beyond

David Vaughan, Director of Science at BAS, says that partnership with ESA to use Halley Research Station in Antarctica can play a part in ensuring astronauts can operate safely on future space missions.

“Offering Halley Research Station as an additional platform for European researchers will provide us with important data, experience and knowledge to prepare for future long-duration human missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond,” said ESA’s Jennifer Ngo-Anh.

Cut off from the world

Explains Halley Research Station doctor Nathalie Pattyn, in a British Antarctic Survey Press Office release: “This experiment will be running at both Concordia and Halley stations to look at the factors affecting astronauts as they embark on long periods in space. Living at Halley is in many ways similar to living in space where crew are cut off from the world without sunlight and in very small communities.”

There is expected to be a huge scientific bonus of comparing data from Halley and Concordia stations, Pattyn concludes, the kind of information useful to appreciate the influence of hypoxia, the lack of oxygen, on top of the isolation and confinement issues.

Pattyn is from Vrije Universiteit Brussel where she is a professor of biological psychology.

Psychological status check

One of the other projects running over the next nine months will involve the team members recording themselves in a video diary.

Diaries will be analyzed via a computer algorithm through parameters such as pitch or word choice.

Researchers expect that this technique will provide a new window to objective monitoring of psychological status, and thus adaptations to the stresses of prolonged space flight.

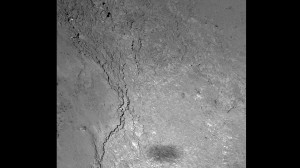

On February 14, 2015, the Optical, Spectroscopic, and Infrared Remote Imaging System (OSIRIS) on the Rosetta spacecraft observed the surface of comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko in the Imhotep region with the Sun directly behind it from an altitude of six kilometers.The image resolution is 11 centimeters per pixel. The orbiter’s shadow is visible as a dark rectangular patch in the lower part of the image.

Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA

Close-up images of comet 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko have been taken by the Optical, Spectroscopic and Infrared Remote Imaging System (OSIRIS) on the Rosetta spacecraft during a recent overflight.

Rosetta is a European Space Agency (ESA) mission with contributions from its member states and NASA.

Recent images show the comet’s terrain – abruptly terraced steps separating flat ground from fissured areas.

Scientists have given this region, which is situated not far from the equator of the larger part of the comet nucleus, the name Imhotep.

Philae landing site, still unknown

According to the DLR, Imhotep is on the opposite side to Philae’s landing site, which means the scientists were denied the possibility of discovering the landing craft’s location during this overflight.

Rosetta’s Philae lander that touched down on the comet is funded by a consortium headed by the German Aerospace Center (Deutsches Zentrum fuer Luft- und Raumfahrt; DLR), the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS), CNES and the Italian Space Agency (ASI).

This image was acquired by the Rosetta Lander Imaging System (ROLIS) on board the Philae Lander from a height of approximately 40 meters, before the first touchdown. The resolution is four centimeters per pixel.

Credit: SA/Rosetta/Philae/ROLIS/DLR

So far, only the Rosetta Lander Imaging System (ROLIS), installed on the bottom of the Philae lander, has been able to acquire higher resolution photographs of the comet’s surface as it descended towards 67P Churyumov-Gerasimenko.Scientists are currently analyzing photographs of the comet’s surface, which were taken immediately after landing using artificial light.

It is hoped that these images will provide definitive information on the celestial body’s fine structure. Preliminary results are expected in April 2015, according to the DLR.

“We are about to…bloon” is part of a campaign request for dollars to help record the first-ever spherical video of an eclipse from the stratosphere.

On March 20th of this year there will be a total solar eclipse. A unique feature of this event is that the Moon’s shadow will sweep over the North Pole – something that occurs once every 500,000 years or so, according to organizers of the balloon project.

“This is our last chance to capture the shadow of the Moon over the northern ice cap before it melts,” say the coordinators of the effort, Zero 2 Infinity based in Spain.

On the day of the eclipse, when the Moon will obscure the Sun, the stars and the planets will become visible and the shadow of the Moon will be seen going over the Earth. The intent of the project is to record this with a spherical camera that will cover a 360º angle.

The visibility of the eclipse, from the only populated areas on the ground, is from Svalbard and the Faroe Islands.

The visibility of the eclipse, from the only populated areas on the ground, Svalbard and the Faroe Islands.

Credit: Zero 2 Infinity

GoPro cameras

A zero-emissions stratospheric balloon will carry GoPro cameras mounted on a rig to record a 360 degree spherical video at an altitude where the view of the Earth and the Sun is very similar to what astronauts experience from the International Space Station.

On the ground participants will receive the video feed into tablet or smart phone and be able to feel as if those taking part were in space – looking out their “window” to see the whole world below.

Want to take part?

The organizers have launched an indiegogo crowdfunding campaign at:

https://www.indiegogo.com/projects/bloon-360view-of-a-total-solar-eclipse-from-space

Also, check out this near-space eclipse project via Vimeo at:

This near-infrared, color mosaic from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows the sun glinting off of Titan’s north polar seas. The view was acquired during Cassini’s August 21, 2014 flyby of Titan.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/University of Idaho

Saturn’s moon Titan may well be a site for life – but “not as we know it” say Cornell University researchers.

While liquid water is a requirement for life on Earth, other, much colder worlds, may harbor life beyond the bounds of water-based chemistry.

Cornell chemical engineers and astronomers offer a template for life that could thrive in a harsh, cold world – specifically Titan, the giant moon of Saturn. That world is awash with seas not of water, but of liquid methane.

Titan could harbor methane-based, oxygen-free cells that metabolize, reproduce and do everything life on Earth does.

Graduate student James Stevenson, astronomer Jonathan Lunine and chemical engineer Paulette Clancy, with a Cassini image of Titan in the foreground of Saturn, and an azotosome, the theorized cell membrane on Titan.

Credit: Jason Koski/University Photography

That prospect is detailed in the Feb. 27 issue of Science Advances, led by chemical molecular dynamics expert Paulette Clancy, the Samuel W. and Diane M. Bodman Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, with first author James Stevenson, a graduate student in chemical engineering.

The paper’s co-author is Jonathan Lunine, the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Astronomy.

Promising compound

According to a Cornell press statement: “On Earth, life is based on the phospholipid bilayer membrane, the strong, permeable, water-based vesicle that houses the organic matter of every cell. A vesicle made from such a membrane is called a liposome. Thus, many astronomers seek extraterrestrial life in what’s called the circumstellar habitable zone, the narrow band around the sun in which liquid water can exist. But what if cells weren’t based on water, but on methane, which has a much lower freezing point?”

Candidate compounds from methane for self-assembly into membrane-like structures were theorized. The most promising compound they found is an acrylonitrile azotosome.

An inhabitant of Titan? A representation of a 9-nanometer azotosome, about the size of a virus, with a piece of the membrane cut away to show the hollow interior.

Credit: James Stevenson

Proof of concept

Their theorized cell membrane is composed of small organic nitrogen compounds and capable of functioning in liquid methane temperatures of 292 degrees below zero.

The azotosome is made from nitrogen, carbon and hydrogen molecules known to exist in the cryogenic seas of Titan, but shows the same stability and flexibility that Earth’s analogous liposome does.

While this initial proof of concept is stirring the creative juices, the next step is to try and demonstrate how these cells would behave in the methane environment – what might be the analogue to reproduction and metabolism in oxygen-free, methane-based cells.

Co-author of the work, Lunine says he looks forward to the long-term prospect of testing these ideas on Titan itself, by “someday sending a probe to float on the seas of this amazing moon and directly sampling the organics.”